The Badass Story of Ada Blackjack, Sole Survivor of a Doomed Arctic Expedition

Of all the badasses filling the winding corridors of history, Ada Blackjack remains a figure of determination and strength in the face of impossible odds.

This article is part of an ongoing series titled “The Badass Story of...” These stories feature inspiring tales of actual people throughout history to inspire the hell out of you.

This issue contains an affiliate link for a book about an incredible woman who survived the impossible. If you make a purchase after clicking the link, we'll earn some money for coffee, which we promise to drink while thinking fondly of you, you beautiful bastard.

On August 19, 1923, an expedition led by explorer Harold Noice arrived on Wrangel Island, a land mass in the Arctic Ocean, just north of Russia between the Chukchi Sea and East Siberian Sea. The polar airmasses offered a bone-chilling welcome to Noice and his team as they descended onto the arctic beaches to complete their task: rescue five missing explorers who had set out to speculatively claim the island for Canada nearly two years before.

Moments later, a figure ran down to the frigid beach toward the rescue team. It was 25-year-old Iñupiaq woman Ada Blackjack, the expedition’s sole survivor.

The Beginning

Of all the badasses filling the winding corridors of history, Ada Blackjack remains a figure of determination and strength in the face of impossible odds.

Ada’s life began Ada Deltuk in 1898 in Spruce Creek, a remote Alaska Native settlement 130 miles south of Anchorage. She was married by 16 and had three children, only one of whom, a son named Bennet, survived infancy. Her husband, Jack Blackjack (yes, Jack Blackjack was really his name), was an abusive asshole and abandoned Ada and Bennet, leaving her penniless.

Facing unimaginable circumstances, Ada walked — fucking walked —more than 40 miles through the Alaskan wilderness from Spruce Creek to Nome. There, she made the difficult decision to place her son in an orphanage while she sought work as a seamstress to earn enough money to get him back.

In 1921, while working as a seamstress in Nome, Blackjack caught wind of world-famous Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson looking for English-speaking Alaska Natives to join an expedition to Wrangle Island. He was offering $50 a month — almost $900 in today’s money — for a team of five to live on the island for two years, securing a claim to the island for Stefansson’s home country of Canada. Blackjack lept at the opportunity, knowing that the money would be more than enough to provide for her son.

Ada committed to joining the excursion along with Allan Crawford, Milton Galle Fred Maurer, and Lorne Knight.

However, as pumped as Stefansson was about the expedition, Ada was shocked when she discovered that he wouldn’t be joining his crew. Like, at all. When it came to the team’s supplies, he assured them there was no need to bring more than six months worth, as there was so much game on the island, they wouldn’t know what to do with it (as the kids say, the motherfucker sounds a bit “sus.”).

The Island in the Arctic

On September 15, 1921, the five explorers were dropped off on Wrangel Island. Blackjack later said that when the ship that brought them there sailed off into the cold horizon, the men celebrated, and she wept.

Scared, isolated, and questioning her decision, Blackjack fell into a depression and neglected her duties of cooking, cleaning, and sewing (we’ve all been there). She endured harassment and abuse from the rest of the crew, who sounded like they were big giant babies who couldn’t handle feeding or cleaning up after themselves. Ada wrote that thoughts of her son strengthened her resolve, and she embraced her work and role on the team.

Months passed, and when summer came, the sea ice broke, and the team eagerly awaited the arrival of a ship that was scheduled to drop off more supplies. But none came over the horizon.

Back home, politics did what they do: ruined everything. The Russians decided to claim Wrangel Island, and the Canadian government, which funded the original voyage, said, “Nah, bro, we don’t want to mess with them.”

Stefansson was left scrambling for new investors while Ada and the rest of the crew faced an Arctic winter with no supplies. The island was not overflowing with game, as Stefansson had promised (lied), and the team struggled to find sustenance. One of the men, Lorne Knight, showed signs of scurvy. Although scurvy sounds like a made-up pirate disease, it is very real, resulting from a lack of vitamin C and causing weakness, skin hemorrhages, anemia, and gum disease.

On January 29, 1923, Galle, Maurer and Crawford decided to take their chances, taking a sleddog team across the sea ice toward Siberia in search of help. They were never seen again.

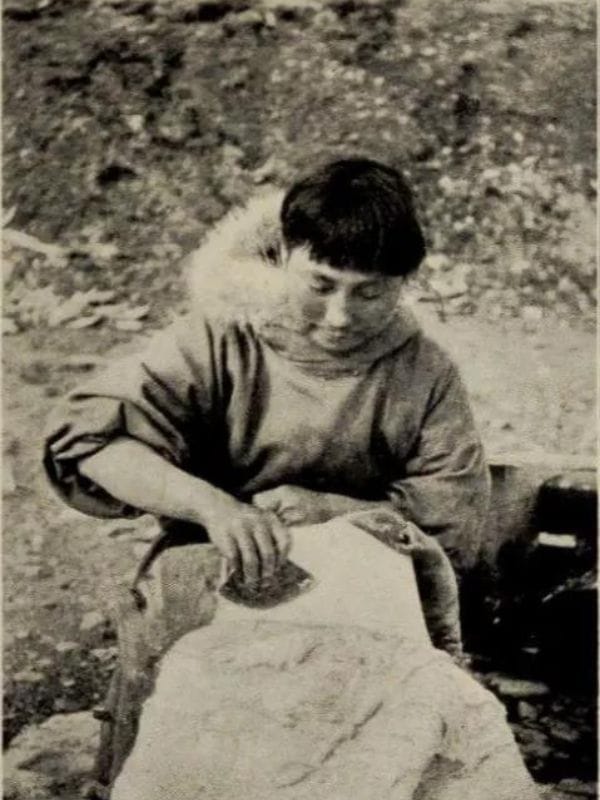

Knight and Ada were alone on the island. With Knight succumbing to scurvy, Ada took sole responsibility for caring for the camp, doing the jobs of four men every single day. She even taught herself how to load and shoot a rifle to hunt game and protect the camp from prowling polar bears. Along with maintaining camp, she cared for Knight, feeding him, tending to his sores and reading to him.

Even while she cared for Knight, he was cruel to her. The pages of her journal describe him berating her as she built a fire, praising her dirtbag husband for leaving her and her child and blaming her for the deaths of her infant children, all of which is a really shitty way to behave to the person that is literally keeping you alive. Despite Ada’s best efforts, Knight passed away on June 23, 1923.

'Have I a dream or not?'

Ada was utterly alone on the island. With no experience in hunting, trapping, or wilderness survival, she quickly adapted and utilized her Iñupiaq knowledge to survive. Her meticulously kept journal shows that she caught food nearly every day, trapping foxes, hunting birds and seals, and collecting gull eggs and vegetation. She chopped wood, secured her shelter from dangerous wildlife, made warm clothes for herself from hides, sewed a pair of slippers, and fashioned a leather school bag strap to give her son Bennet when she returned.

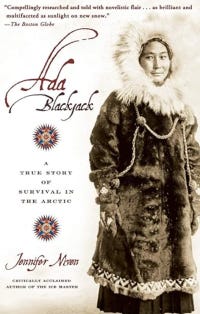

According to “Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic” by Jennifer Niven, Ada built a gun rack above her bed so as not to be caught unarmed should a polar bear prowl too close to camp.

She even made a fucking canvas boat to travel to a small nearby island and to collect more food.

Ada’s journal reflects that she was active every single day on Wrangle Island, throwing herself into survival in the hopes she would be reunited with her son. Even on the days when she was snow-blind and the wind was blowing too hard for her to leave her shelter safely, she cleaned the hides of animals she caught, read, tidied, made herself tea, and journaled.

There were times when she felt death looming over her. On June 10, 1923, she wrote that if it came for her, she wanted her sister Rita to care for Bennet.

On August 19, 1923, two years after Ada stepped onto Wrangel Island, Noice’s team arrived on its shores.

In a recounting of the rescue printed in 1924, The Seward Daily News reported that Ada heard the noise of the men arriving, and she burst out of her shelter, running onto the frigid beach toward their ship. She ran and cried, “Have I a dream or not?”

Captain Hans Olson, who knew Ada from Nome, caught her in his arms and said, “Ada, you have no dream, and we are here to take you away.”

The crew was astonished at Ada’s survival, noting that her command of her environment was such that they suspected she could have lived on the island another year if not for the psychological effects of isolation.

Noice was a racist asshole and alleged that Knight died due to Ada’s lack of care. He also publically suspected that she was pregnant via one of her crewmates. Olson shut Noice the fuck down, saying that Ada was indispensable to the team and a highly regarded community member in Nome. The Seward Daily News wrote that upon returning to Alaska, Noice kept up with his bullshit and immediately threw shade at Ada. Still, she was defended by the community that knew her to be a kind woman and devoted mother.

For the rest of her life, Ada was the subject of constant press attention and the disgusting racism toward Alaska Natives and Native Americans that permeated the time period. Stefansson and Noice exploited her story for their benefit, both writing books about her survival. Ada received no financial compensation from either of them. Some newspapers from the time stated Ada received a warm welcome home. Still, rumors started by Noice that she was responsible for Knight’s death persisted, and she was even accused of cannibalizing her crewmates.

Hailed as a female “Robinson Crusoe,” — which implies that Ada threw caution to the wind in the pursuit of adventure and was not essentially abandoned by Stefansson due to his incompetent risk assessment and mismanagement of the expedition — Ada rejected all the attention she received for a quiet life.

After she collected her earnings from Stefansson, reportedly less than he initially agreed to pay her, she collected Bennet and moved to Seattle. She later had another son and moved back to Alaska, where she lived until her death at 85.

Read More

What an absolute badass, huh? Ada's inspiring story is more than we could ever fit in our humble newsletter. Learn more about Ada's incredible life in "Ada Blackjack, a True Story of Survival in the Arctic" by Jennifer Niven.

Ada’s journal from her time on Wrangel Island can be read here.

Watch "Ada Blackjack Rising," a short film featuring an Alaska Native woman reflecting on the story of Ada Blackjack.